by Kanti V. Mardia and Aidan Rankin

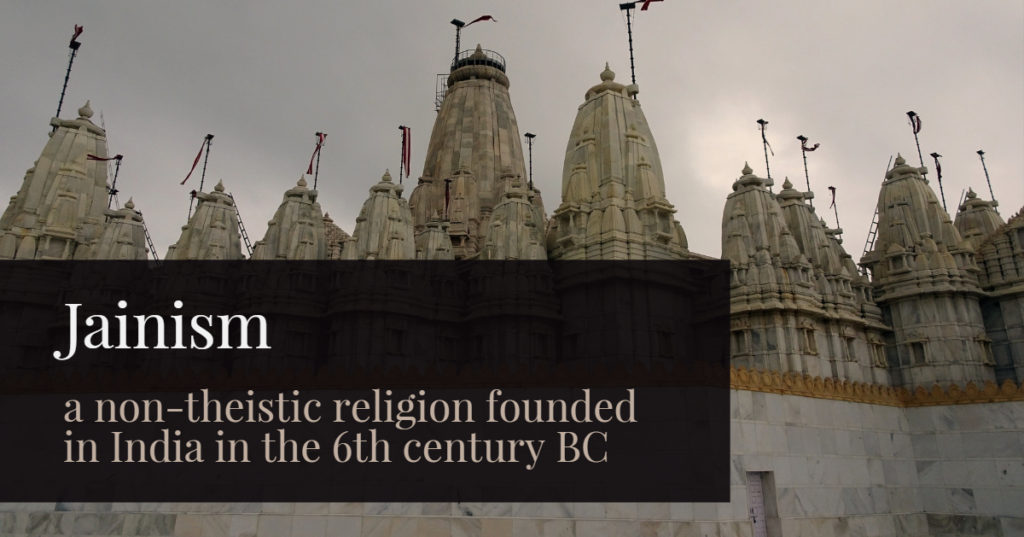

Loosely speaking, Jainism was founded by human spiritual guides known as Tirthankaras. This word means ford-makers, path-finders: those who point the way through or the way ahead. Tirthankaras are, therefore, the people who show us the true way across the troubled ocean of life, the leaders on a spiritual path.

They lead by example and wise counsel. They unlock knowledge by training our (and their own) minds to think in ways that point towards spiritual awareness and a sense of the real self.

In all, there were twenty-four Tirthankaras. The first of these was Rishava, an ancient lawgiver who, according to one Jain text, lived ‘many thousands of years’ ago. This implies that he lived before reliable recorded histories began and so he can be seen as a semi-mythological figure, somewhat like Lycurgus for the ancient Spartans. Rishava is recognized by some Hindus as a manifestation of the divinity Shiva – an illustration of the complex relationship between the Jain path and the Vedic or Hindu tradition, to which we shall later refer. It seems that Rishava as lawgiver was able to fashion out of several nomadic communities a settled, pacific society, based on the cultivation of grain, with cities, currency, trade and a common legal system. Those familiar with the Jewish or Christian traditions might find parallels with the figure of Moses.

Rishava appears eventually to have abandoned political power and material possessions in favor of the life of austerity and wandering. He came to identify material and worldly concerns with spiritual bondage, which Jains have come to think of as karmic bondage. In this, he set a precedent for other Tirthankaras and established the pattern of thought and the priorities familiar to Jains ever since. That is to say, he favored civilization, justice and knowledge over barbarism, chaos and ignorance. However, he also sought out a spiritual path beyond both the pre-conscious state of ignorance and the artifices of a sophisticated urban society. The former precluded enlightenment or rational thought. The latter provided insidious distractions and delusions of grandeur that became powerful obstacles to spiritual advancement.

This insight gives rise to a new interpretation of power, which is not based on controlling and subjugating others, acquiring material ‘things’ or claiming a monopoly of truth. In contrast to the conventional, outward vision of power, it is an inward vision, consciously repudiating the trappings of status and embracing humility. Yet it is also a more supple, flexible and enduring form of power that outlasts states, politicians and the wealthy. Such an interpretation of power matches the understanding of ‘conquest’ implicit in the term ‘Spiritual Victor’. The struggle is for control of the territories within rather than geographical expansion or personal gain, as we usually understand conquest. These counter-cultural definitions of power and conquest are linked to an inclusive definition of wisdom as the open-minded pursuit of wisdom and insight into the workings of the universe and our place within it. Rational thought, meditation and the conquest of superficial desires can give us a sense of proportion. They bring us closer to an understanding of what is truly important in life, in place of the material cravings and ambitions that so easily bind us. This sense of equanimity is central to Jainness.

The spiritual discipline of Rishva was followed by twentyone successive Tirthankaras until, in the age of the 23rd Tirthankara, Parshva, the tradition that we now call ‘Jainism’ began to appear in a form recognizable to us today. Parshva is also the first of the Tirthankaras whose historical existence as a human being can be verified reliably. He is generally held to have lived around 2800 years ago (traditionally dated 872-772 BCE). The philosophy and logic of modern Jainism emerged in a systematized form at the time of the 24th Tirthankara, Mahavira, who was born in 559 BCE and whose nirvana (full enlightenment) took place in 527 BCE. Mahavira means ‘Great Hero’, a name symbolic of spiritual victory through non-violence and the refusal of conventional power or wealth. He was a contemporary of Gautama Buddha (563-483 BCE), the overlap being thirty-six years, but there is no evidence that they ever met. It is also worth noting that the Buddha was in the process of enlightenment at the time when Mahavira was at the peak of his career (for a more detailed account of Mahavira’s life, see Appendix 1).

Even today, it is still not unusual for these two great spiritual teachers to be confused and conflated. It is sometimes claimed (against all available evidence) that Buddha and Mahavira were one and the same, or that Jainism is really a subset of Buddhism, which is far better known outside Indic civilization. There are many differences, both obvious and subtle, between the two philosophies, as well as areas of common ground, but such comparisons lie outside the scope of this study. In iconography, a simple distinction can be made by clothes: Mahavira is usually naked, whereas the Buddha is usually clothed! Icons of Parshva and other Tirthankaras are also frequently found in Jain homes and places of assembly.

To bring the dates of Mahavira and Gautama Buddha into a western perspective, we may note that Aristotle was born in 384 BCE and Jesus Christ around 4 BCE. India officially celebrated the 2500th anniversary of Mahavira’s nirvana between 13th November 1974 and 4th November 1975. One of the strongest admirers of the Jain religion was Mahatma Gandhi, whose thoughts and actions were greatly influenced by certain Jains, in particular Raychandbhai (Raychandbhai Mehta, also known as Shrimad Rajchandra). Gandhi was inspired by Jain doctrines of non-violence, respect for life, ecological responsibility and the value of each individual. He applied these teachings to his strategy of Satyagraha (‘truth-struggle’) and non-violent resistance to British colonial rule. They also helped him shape his economic philosophy of swadeshi: self-sufficiency through cooperatives and local production for local need. While embracing many Jain ideas, Gandhi remained a devout Hindu and indeed credits his Jain guides with increasing his understanding of what Hinduism was really about. The evolution of Gandhi’s thought is surely one of the clearest illustrations of how Jainness works.

Mahavira is often erroneously referred to as the ‘founder’ of Jainism. In reality, he sculpted a new form from material that had already been long in existence. Jainism has evolved out of the most ancient Indic spiritual teachings, which are in turn aspects of the earliest human consciousness of the universe. Living as a Jain implies awareness of Dharma, which is at once a natural law governing the workings of the universe and an ethical system showing us how we should live. Spiritual practice and the pursuit of knowledge bring us into closer alignment with Dharma.

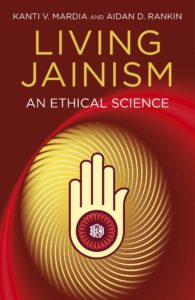

Living Jainism, Aidan Rankin and Kanti Mardia,

978-1-78099-912-8 (Paperback) £12.99 $22.95 , 978-1-78099-911-1 (eBook) £6.99 $9.99

Living Jainism explores a system of thought that unites ethics with rational thought, in which each individual is his or her own guru and social conscience extends beyond human society to animals, plants and the whole of the natural world. The Jain Dharma is a humane and scientific spiritual pathway that has universal significance. With the re-emergence of India as a world power, Jain wisdom deserves to be better known so that it can play a creative role in global affairs. Living Jainism reveals the relevance of Jain teachings to scientific research and human society, as well as our journey towards understanding ourselves and our place in the universe.

Essential reading for anyone interested in the philosophy of Jainism for our time David Lorimer, Scientific and Medical Network

Exquisite scholarship … I cannot recommend this book more highly Rev. Lynne Sedgmore CBE

An outstanding book from two very talented scholars of Jain philosophy and wisdom Dr Atul K. Shah

Kanti Mardia is Senior Research Professor in Statistics at Leeds University, UK., as well as having five higher degrees and various professional fellowships. He is President of the Yorkshire Jain Foundation and his previous Jain-related books include The Scientific Foundations of Jainism and Jain Thoughts and Prayers.

Aidan Rankin is a London-based writer whose books include Many-Sided Wisdom: A New Politics of the Spirit, Shinto: A Celebration of Life and The Jain Path: Ancient Wisdom for the West. He has PhD and MSc degrees in Political Science from the London School of Economics and an MA in Modern History from Oxford University

Categories:

0 comments on this article